Thoughts From The Arthur Kill Train Station

In this essay, Brian Buchanan moves between video games, public transit, and life on Staten Island’s South Shore to explore how movement shapes memory, identity, and belonging. From digital “fast travel” to the lived rituals of the Staten Island Railway, it blends cultural commentary, local history, and personal reflection to consider what we gain, what we lose, and who we become when the journey gets easier, but the distance still matters.

part I: fast travel

For those that don’t know, uh, Christmas is a holiday in the Christian tradition that is recognizable, in part, by the ritualistic exchange of heartfelt gifts between the friends and family of practitioners. Billions participate. Part of the joy is seeking out or crafting the right gift for the right person. Anticipation snowballs throughout the year as these special bonds are enriched, and it all culminates on the big, celebratory day: December 25th… unless you’re a tech conglomerate. For them, every day is Christmas. We wantonly stuff their stockings with the most private and intimate details of our lives. For a few years now, they’ve put fancy wrapping paper on all this data and set it under our Christmas trees as our ‘Year In Review.’ Spotify was the first company I can remember doing something like this with their Wrapped campaign—which I’m sure has generated billions in the free marketing they’ve wrung from their customers—but others have caught the bug, as well. Apple Music, YouTube, Discord… you name it. A few weeks ago, I found it especially hilarious when I got a notification from—of all places—the Xbox achievement tracking website TrueAchievements.

I’m not much of a gamer and now I have the (depressing) stats to back it up. Apparently, my most played game last year was Bethesda’s Starfield—I sunk 36 hours into it, mostly over the course of one long weekend in late June. Maybe that sounds like a steep commitment for a single game, but it’s actually a paltry amount for the type of game I enjoy the most: open-world RPGs, or role-playing games. Bethesda Game Studios have built their name on creating such games with fantasy, post-apocalyptic, and now—with the release of Starfield in 2023—sci-fi settings. What makes these games appealing is that, while there is usually a sprawling main quest, the real story is the one you make for yourself. Take their blockbuster hit from 2011, Skyrim. Players can fulfill their destiny and become the Dragonborn or pick sides in a morally complex civil war. Is that what I did? No—I didn’t have to! The world’s landscape is so enormous and detailed, I poured hundreds of hours into simply travelling to each remote village and every hidden cave. I wouldn’t go into these villages or caves, I was only chasing the dopamine hit of filling out my player map. Oh? What’s that? You’ve never cosplayed as a cartographer or a glorified Michelin Guide pamphlet writer in your fantasy RPG???

It was an exercise in unwinding, and the low stakes/relaxing quality is what made it fun. That said, this tedious task did serve a secondary function. Often in these ginormous open world games, you’re allowed to ‘fast travel’ to locations after you’ve discovered them, meaning you can instantly warp across cities, continents, or even worlds in seconds. This feature has saved me literal days of my life, but its mere existence is a source of major contention among RPG purists. Their objection is that in these worlds of magic and dragons, fast travelling is immersion breaking, violating the Aristotelian law of improbable possibilities. Bethesda compromises. For example, in Skyrim, you can hire a carriage driver outside Whiterun to take you to the major cultural hubs of Solitude or Riften. It’s the same thing as fast travelling, functionally speaking, but I guess you can more easily justify your role-playing if you're spending your in-game money and can pretend you’re taking a nap on the bumpy ride or something.

Since its release, Starfield has had—charitably speaking—mixed reviews. There are dozens of star systems and a thousand worlds to explore, purportedly, and one sliver of criticism (there are many) is that it is too easy to traverse between these worlds via fast travel. The spaceships in Starfield come with standard sci-fi Grav Drives, spacetime warping engines that allow for faster-than-light travel, and after a brief, black loading screen—zip!—you’re wherever you want to be. For the first time ever, I feel myself erring on the side of the purists. The in-world justification for such a far-fetched technology isn’t what I find so objectionable—on the contrary, actually: in a game where ‘fast travel’ has reached its zenith in application, where the line between mechanic and metaphor has been completely erased, its application has become utterly irrelevant. You can trigger this instantaneous travel anywhere, at any time. The game just assumes for me that my character treks down to their ship, hops into the cockpit, launches into orbit, punches it to the Alpha Centauri system, lands, exits, then traverses across an entire city to my penthouse apartment. But I never have to do any of that, and it’s just a stretch too far for me. There should be friction between me and where I want to go. At least some, a little bit. How else are you supposed to appreciate a destination if there isn’t any journey?

ANYWAY the concept of ‘fast travel’ has been on my mind quite a bit recently, sparked by the election of Zohran Mamdani and his plans to make all the buses in New York City free. Truly: one cannot live on Staten Island without imagining all the transportation pasts we could’ve had or what might yet come pass, both scenarios as fantastical as the medieval Skyrim or the future-forward Starfield. The friction traversing New York city generally and Staten Island specifically today is crushing in its excess. Just after trashing it, I can’t help but daydream about having Starfield’s FTL travel in real life. Should this free bus initiative become a reality—and I’ll throw my chips down: I hope it does—I’m curious to see the effect(s) it has on traversing our little-borough-that-could. I’ve watched too many TikTokers cherrypick and manipulate what esoteric transit data is available (each making their case for the efficacy (or not) of a free bus) to make my own considered prediction. What I am so thoroughly comfortable discussing, though, is the rhetoric used to promote this plan… and the backlash.

part II: sir, this is the SIR

The ferry is how Staten Island is known to the world. Joni Mitchell, Billy Joel, Bob Dylan, and John Lennon have each made mention of it in their songs. CGI Spiderman once failed to save the Spirit of America. And there is now, I swear to God, a Magic: the Gathering card of the ferry. So when it came time to pitch the city on the merits of free transportation (and to Staten Islanders in particular) the perennial fight took on an unmistakably orange, nautical flair. The ensuing “discourse” has been laughably predictable. As is tradition: Staten Islanders had their severe allergic reaction to the whiff of the “S” word, and the rest of the city dunked on us via Threads and TikTok. Rant: have you ever noticed that Staten Island’s online detractors always say the same exact thing? Invariably, someone in the comments will say, “We—the rest of real New York—do not claim Staten Island.” Then someone else will say, “We should just give them to New Jersey!” And then someone from New Jersey says, “We don’t want them, either!!!” I’ve seen this exact exchange acted only a million and one times, as if it were Masterpiece Theatre on loop, forever. People of the internet, I’m begging you: have one original thought and rummage up some new material, would you please???

As a New York icon, the ferry was the obvious vessel for this debate. I’m not so sure it was the most resonant rhetoric; the Staten Islanders most staunchly opposed to free public transportation aren’t the ones using the ferry. I mean, I can imagine some wall street bros might ride it ironically, maybe. Rider demographic info has proved difficult to track down. No matter: there was a second option the Mamdani campaign could’ve instead centered the virtues of this proposal around, which is kind of amazing. I’m talking, of course, about the Staten Island Railway, our sole train line that is also free (mostly). Notably, it serves the eastern and southern portions of Staten Island.

I do not want to take the SIR to prom, and like Tony Soprano says, “Remember when is the lowest form of conversation.” Concessions aside, I find the SIR is inherently romantic—how could I not? Picture a Friday night in the mid 2000s: in the Tottenville Square, on the corner of Amboy and Page, is a Burger King. And a Burger King unlike any other, for it has—bizarrely?—a sports theme. We start there at sunset, sitting among the (fake?) memorabilia, waiting to see who might show up. From there, plans are drawn up, and they almost always involve walking south past the Bethel cemetery and boarding the train at Nassau Station. Growing up, we have three stations within my zip code, and Tottenville Station proper is the social hub in town, two stops down. This is an easy target destination for ‘out-of-towners’ to meet up with us, too: “Just go all the way to the end of the line!” From there, you’ll find friends grabbing pizza at the top of Main Street, or somewhere along the routes to the Conference House or Tottenville Shore Parks. We roam around accumulating people, friends of friends of friends, and the train allows us to cover most of the town in a short amount of time. We amass a lion pride.

Travelling northbound out of town was an even bigger deal. Equipped with only a couple coins found between couch cushions, my friends and I would hop on at Nassau and ride up to Pleasant Plains to get Ralph’s Ices (when we weren’t in the mood for Egger’s soft serve). I only told my parents I was taking the train after it was a settled, established fact; young gallivanters learn quickly that it’s better to beg forgiveness than to ask permission. Still, it was a mark of independence, trust, and maturity that I was allowed to keep going. Embedded in all these trips was ‘the hang’ at the stations: odd as it might sound, we socialized at these liminal spaces, waiting for the only form of ‘fast travel’ available to us. These trains—not just the places they occupy, but their use—served as the backdrop for some of our most pivotable moments. I know this is true not just for those of us down in Tottenville, either. I’m aping the title of this article from two Curious Volume songs—Thoughts from the Eltingville and Annadale Train Stations—that are products of this same, near sacred understanding. For young Staten Islanders with easy SIR access, these were our sanctuaries, your station: a shibboleth.

None of that would’ve been possible if the trains weren’t free—we wouldn’t have gone to the stations or ridden the trains otherwise. Sure, we could’ve just walked twenty minutes home across town at the end of the night, but we had a better option. And yes, like many American teenagers, our first delicious taste of true freedom came junior year. Being able to go anywhere at any time in a car was both unprecedented and alluring. Attitudes changed. Overnight, the SIR became transportation for little kids and peasants, and our memory of the train cars was that they always smelt of fresh piss. I’m sure in all my waxing poetic above I’ve forgotten all the times I waited endlessly long in the sticky hot for a train without knowing if or when it would ever show up. Life happened on the train, and not all of it was good. The SIR is a museum of loneliness and heartbreak, too.

Ultimately, the point of any train is to get people from Point A to Point B reliably. Yet: I’d be a hypocrite without wishing for more, for The Youth™ across the city to have the gift of adventure and wonder enabled by hopping on a free train or a free boat or, maybe soon, a free bus. I get it: you can’t measure the ROI on something like that—on becoming unbound—but that doesn’t mean it isn’t real or meaningful or worth our investment. What it comes down to is this: a vote for free transportation is a statement of faith in my community. Writing this out, it’s clear that such an idyllic notion of the SIR would be too naïve, nuanced, and niche a story to sell when persuading voters, but that’s OK. I enjoy getting lost in stupid, unimportant hypotheticals like this. I’m sure I picked up this trait on short train rides across town, after waiting bored at Nassau Station.

part III: a tottenville art survey

If you have the patience and the stomach to wade into the second layer of generic Staten Island discourse online, you begin to notice even more familiar trends. Namely, when Ohio transplants (why are they always from Ohio?) decide that Staten Island would be better off sunk at sea, it triggers knee-jerk reactions from the North Shore apologists. They always invoke the Wu-Tang Clan before condemning the South Shore as the actual bad section, overrun with racists and fascists. We are all of us: rude, tacky, loud, inbred. We’re busybodies in need of a driving lesson. There is no fun here, there is no culture, only drug habits and I guess just a massive amount of hot air. I used to get defensive and I’d always take the bait. These days I try to remember that these social media algorithms are designed to keep us engaged, and nothing steals our attention quite like being told whom to fear and what to hate.

I might find their platforms poor, their rhetoric lacking, and their historical context missing whenever the South Shore gets rebranded as New Hell—especially by other Islanders—but to be clear: I agree with the heart of what they say. That, and I don’t know any other way to be open to change than by listening to people and believing them when they share anecdotes about their lived experiences. On the topic of culture and the arts, however, I can see it for myself: we are an oasis down here. I mean, has anyone wasted more ink lamenting the South Shore’s nonexistent music scene than me? And that’s just the art scene I’m tapped into. What about the others? Are there any? I feel like I would have some inkling of anything. I do live here after all.

I decided I ought to do an art survey of Tottenville. You know, good old fashioned field work. Gather up some data. If I’m going to make any proclamations about my town or the South Shore more broadly, I figure I better back up what I’m saying with evidence. After some consideration, I came to this idea which, if not completely fair, then is at least reasonable: a place that values art ought to have art on display. That’s non-controversial, right? The more of it they have, the better. I took to the streets—my streets—to really look and see what we have.

A few caveats:

What are Tottenville’s city limits? I’ve always considered the yellow lines of Page Ave. and Richmond Valley Road as being where Tottenville ends. That and the, uh, Raritan Bay. This is a little awkward for places like Tottenville Bagels, which should technically be Richmond Valley Bagels in my mind, but hey, I have to stop somewhere and what do you know? The Transportation Department has decided for me! This means: no Aesop Park statues, not that weird abstract piece outside the front of PS6, and not the terrifying twig configurations in Long Pond Park.

I’m leaving out homes and business structures. This might sound like a cop out, since, if Tottenville is renowned for anything in the modern age, it’s our charmingly antiquated architecture. For this experiment, though, I wanted to center art for art’s sake. Put another way, architecture is art, but the primary purpose of a house is the four walls and the roof. It’s like fashion: our choice in style plays an important role in social signaling, but it isn’t strictly necessary to survive. And who knows, maybe one day I will write as many as one (1) more photo essays based just on Tottenville’s most aesthetically pleasing homes.

In a similar vein, whatever I consider ‘public art’ is obviously arbitrary. There are multiple dancing schools in town. All the choreography and performances? That’s art. There are many exquisite restaurants in town—you’re not going to catch me saying that what those chefs do isn’t art. “There are cathedrals everywhere for those with the eyes to see,” is a wonderful sentiment (until you find out who popularized it in the modern era, sheesh), such as nature’s “art” in the parks. I specifically tried to limit myself to art that was divorced from any commerce. All art has ulterior motives of some sort, sinister or otherwise. As much as possible, I searched for art that was just existing.

I’m not a photographer. I shot all these photos on my phone.

Last but not least, this is the Shaolin Art Party, not the Shaolin Art Dissertation—let’s have some fun with this.

So, ahem, without any further delay, here’s what I found:

The South Pole. Tottenville is the southernmost town in New York City. In Conference House Park is a pole that celebrates this fact. It sits at the end of a path, just before the beach. According to my uncle—who is a member of the Conference House Park Conservancy—the pole was moved once, so actually all it sits on is a throne of lies. I like that, despite the excessive fading, it’s striped up as a candy cane for the holidays. During the pandemic, I became slightly obsessed with how the pole was being vandalized. All I saw this time was someone put a Sticki Rolls sticker on it.

The number of houses of worship in Tottenville is absurd:

The Bethel United Methodist Church

Our Lady Help of Christians Church

The Tottenville Evangelical Free Church

The House on the Rock Church

The Coptic Orthodox Church

The Korean Church of Staten Island

The South Baptist Church

Virgin Mary & St. George Coptic Orthodox Church

St. Paul’s United Methodist Church

Chabad of Tottenville (the temple on Amboy)

Those are just the ones I can remember off the top of my head—there are probably more. While the architecture on some of these buildings is exquisite—St. Paul’s pictured above looks something straight out of Oblivion—I’m disqualifying them for the same reason as homes or other buildings. That said, this bell tower is technically an independent structure, and dope. I don’t think it ever rings—sad. Next!

The Veteran’s Memorial. Located across the street from St. Paul’s, this memorial is quaint but dignified. Obelisks are never not sick. I do wish this space was bigger than the literal recycling bin right behind it.

The 9/11 Memorial Clock. Sitting at the corner of Amboy and Main Street, this clock is both unmissable and awesome. A clock feels like an especially fitting tribute to those that are no longer here, every tick a reminder of the widening the gap between us and them. A clock like this, with its larger, Roman numerals is old fashioned in a world of SmartPhones and SmartWatches—another clue of time gone by. Lastly, it has four faces in the four cardinal directions, both projecting and welcoming. If you’re ever down in Tottenville, please spend some time—measure it—in reflection.

The American Flag Mural. Across the street from the memorial clock is undoubtedly the work of local artist, and professional provocateur, Scott LoBaido. Large, colorful murals on the sides of businesses get a big thumbs up from me, and it’s hard not to stand beside this work and feel its immensity in the suggestion of wild fluttering. That said, I’ve always felt there’s been something restrictive about these flag murals, wavering in perfect sinusoids; if they’re to represent American ideals, how can they be reached or attained by those of us that are imperfect Americans?

Something is better than nothing, I guess, and the more time we spend engaging in public art, perhaps the easier it’ll be to note the irony of literally drawing lines in the street, as if we lived in a western.

One of my favorite locations in the world to have a think and wonder is the spot at the bottom of Bentley Street, where the south side of the Tottenville Train Station lets out. When I was growing up, one of my aunts had, in her kitchen, a two-dimensional village of homes that sat on the chair rail. Sitting there, on the graveyard of what I believe was the old ferry wharf and looking off at Perth Amboy, New Jersey reminds me of sitting at her kitchen table.

There’s also a nice view of my bridge, the Outerbridge Crossing.

There is also this absolutely magical building across the water that looks like heaven when it is lit up at night. This building is such a perfect sight for me, that I will never be able to go visit it, lest I break the illusion and see the cracks in its stone up close.

OK, so what’s the actual art here? Well, this location has some of Tottenville’s only graffiti.

Note not just the spray paint, but the stickers on the sign, too. What I’ve always admired about graffiti is the conversation between artists over time, making use of the same space over and over again, mixing styles and techniques.

The placement of this art is, like graffiti, a form of protest in and of itself. It sits beyond the safety rails, on cracked pavement. View it—and its messages—at your own risk.

There’s also this piece on the pavement: the name Biden encased in the universal no symbol. I’ve had to tweak this photo in post-production quite a bit so that the work is legible at all. The art has weathered over time and faded on the pavement, leaving one to question if the artist’s intent was a more fundamental exegesis regarding a futile or ephemeral quality of political messaging over time.

Moving on, there is this statue of The Madonna and Child outside the old OLHC school building. I went to St. Joseph by-the-Sea High School, and my Morality teacher senior year showed us a petrifying documentary with video “proof” of Marion apparitions. To this day, encountering such an apparition is my most deeply-seated irrational fear. As a result, when walking through town, I avoid looking at this statue lest it begin weeping tears of blood. People say, “Good art is often uncomfortable.” I agree. But I don’t think this is what people have in mind when they invoke that particular axiom.

Across the street at PS1, and behind a fence, is a golden statue of an eagle. This is PS1 and the neighboring IS34’s mascot, though it does feel a tad idolatrous, right? The rocks in front of it are a nice touch. This is my favorite rock:

There are (at least?) two (!!) more LoBaido murals in town: one on the door to the firehouse and one on the facade of IS34.

I’d like to call your attention, though, to the A. D. letters imprinted in the schoolbook. This is a memorial to Angela Dresch, a charming eighth grader who passed away during Hurricane Sandy. Whenever I walk by, I’m reminded of Tottenville’s response to that storm. When people’s clothes and tax information and journals were strewn all over the Lenape Playground park, and while Mayor Bloomberg was still idiotically considering holding the New York City Marathon, I remember walking into OLHC’s auditorium and seeing innumerable baskets of donations lining the stage, ready for any and all who needed.

There is a statue within the South Shore Little League of Joseph Verdino Jr., a young slugger who passed away in 2007. My picture here does not do the statue justice at all—I was not able to enter the grounds since it is the middle of winter as I write this article—so I implore you to view better photos here. Or better yet, come see it for yourself in person in the spring. There are many institutions in Tottenville—religious, political, or otherwise—but by all accounts, Joseph loved to his core the most crucial institution for us kids growing up in Tottenville: baseball.

I’d be remiss if I did not include in my survey the cemetery at The Bethel United Methodist Church. Too bad I won’t be talking about its glorious facade:

There are too many gravestones and statues to document here—for example, there are several obelisks in there!—but the eye-catcher throughout my whole life has been this statue, right outside the front doors.

Beautiful.

Outside the Tottenville Pool is this signage:

I’m not sure if this is a Tottenville Pool exclusive. I feel like I’ve seen the city reappropriate this style before. Still, I dig it. It’s retro. There’s something sharp about it being a perfect square. I appreciate the choice to spell Tottenville with a lowercase t. I like that it serves as a dividing line between the pavement and the park nearby. Ten out of ten, no notes.

That’s it (almost). That’s (almost) all the public art I could find in Tottenville. There’s a fatal flaw with my initial premise in that, having lived nowhere else on the South Shore, I have no benchmark to say if we’re running an art deficit or if we have an overabundance of public art. Probably: we’re average. This wasn’t a pointless scavenger hunt, however. I do truly appreciate all the art in town better than I did before, and there’s more connective tissue between all the various pieces than I realized.

A majority of this art is some type of memorial, patriotic in nature, or both. I’m still figuring out how that sits with me. I like that there is rich history here, and there’s virtue in remembering those that came before us, real-life human examples of people that did it better, whose memory can be a guiding light. At the same time, I’m cautious of a dollhouse-like effect, as if Tottenville is truly as our naysayers would characterize us: a place stuck in time, inside a bubble. Consider this picture I took between PS1 and IS34.

Many of the fire hydrants in town are painted like this. I like it, the pop of vibrant colors. This simple initiative has given a new, delightful purpose to ordinary public infrastructure. More please. But like… does it always have to be so star-spangled awesome? So much of our art is self-referentially American that I’m left to wonder if we could accomplish that same thing if—instead of painting massive murals again and again—we simply put up a series of mirrors everywhere to go look at ourselves all the time. Perhaps I’m obtusely trying to avoid saying something about vanity, of my own and that of my neighbors. Could there be another way to reflect Tottenville back onto itself that was additionally authentic, that pulled together our nature and architecture and art, that grasped for more?

There just might be an answer at the Arthur Kill Station.

part iv: tottenville sun, tottenville sky

Jenna Lucente’s origin story is as classic as they come: “I was born in Brooklyn, raised in Staten Island.” An art teacher at Susan Wagner High School—a Mr. Joseph Hijuelos—proved instrumental in cultivating Jenna’s artistic taste. “[Mr. Hijuelos] was very influential on us—he even took us to galleries in Soho. We would meet at the ferry and he would take us to see art in the city.” After majoring in painting at Syracuse University—”for better or for worse”—and then attaining an MFA at CUNY Queens College, Jenna began working in publishing. “But in the meantime, I had been making my artwork all along,” Jenna says, adding that at that time, “Being a New Yorker who traveled the subway system, I had always seen the artwork.” Around the year 2000, someone from the MTA came across her work in a public art registry, which led to an opportunity to pitch for the Neptune Avenue Station in Brooklyn. “I did not get that commission, but ever since then, I was like, ‘I will apply for every single MTA opportunity that comes my way.’” Fast forward to 2013 and, persistent as ever, Jenna saw the MTA’s call for artists re: the soon-to-be-constructed Arthur Kill Station.

The process for landing an MTA commission, as Jenna described it to me, is more marathon than sprint. Once the call goes out, hundreds will apply. From there, only five will get called in. “They'll show you some of the specs, like this is what we're looking for, whether it's glass, mosaic, metalwork. ‘This is your budget.’ Basically they're like, ‘Here's your information, we'll see you in six weeks with your presentation.’” Jenna, now a college professor living in Delaware, graciously shared a presentation with me that included many of the materials provided to her by the MTA, which included technical specifications and a thoroughly detailed rendering from the architect. Part of the process included a field trip: “There was no station there when this was proposed to us. They took us to look at an abandoned lot, basically.”

Instead of diving straight into the mechanical details of such a major undertaking, Jenna started gathering inspiration by walking around Tottenville. “I knew that anything that I created had to be for the community. It couldn't be my own agenda, it had to be for the community. It had to be referential of the geography, and that it had to be known.” Four trips and thousands of photographs later, the core ideas of the project began taking shape. Jenna wanted to show a bridge—only a metaphorical one, for now—between Tottenville’s many eras, and found clever inspiration in our town’s architecture. “I started creating a specific frame that referenced the architecture that I saw in those houses. … I really started focusing in more on the framing as an element.”

With this artistic anchor set, the project’s medium began to dictate its direction, enriching the work thematically as it went. Specifically, the use of triple laminate glass layered together resonated with Jenna’s vision. “I had been working with Mylar at the time, which is like a see-through, transparent drafting material. … I wanted to frame it in the past with a foot in the present, and that had to do with the layering. … The background, that more faded image was some kind of historic image, like Outerbridge Crossing; in the foreground, including some kind of native bird [such as an] egret, or plants.”

After the six weeks of exploring, planning, and creating, Jenna pitched her plan to the MTA. “So my proposal to them was this, right? That it would be the sun, the sky, it would be clarity, memory, unity, balance, the Conference House, the Outerbridge Crossing, historic architecture, animal life, including fish and egrets, the shoreline.” Spoiler alert: Jenna was chosen from the five finalists, and her work— titled Tottenville Sun, Tottenville Sky—was set to become a reality. In some ways, though, this was only the beginning; the life of an artist is defined by revision. Jenna shared with me an early design with big, blue maple leaves and lamp in front of the Conference House that didn’t survive to the end. “Along the way, I'm meeting with the MTA and they're like, ‘How about a little more of this, a little less of this, we don't like that, we don't like this, how about this?’ It was interesting, because they actually pushed me pretty hard to get things where they needed to be.”

Eventually the designs were finalized, and Jenna converted all her manual artwork—the Mylar painting, the drawings, and the manipulated photography—into ginormous, life-size versions in Illustrator. These digital files were then zipped to an MTA approved glass fabricator in Germany. “I went over there to kind of check on the progress, but the MTA was guiding the whole thing. And then, of course, we ended up with the project as you know it.”

In the end, Tottenville Sun, Tottenville Sky demanded every tool in the artist’s toolbox, yielding—when Arthur Kill Station finally opened in January 2017—something genuinely worth being proud of. “I used every single skill that I had, ranging from drawing, painting, photography, digital skills, color skills, like every single skill to make this happen. Part of my joy in this project was I was like, ‘Are they going to really let me make a giant bird head? You know, that you round the corner and see like a giant eight-foot bird head?’ And the answer is yes!”

part v: thoughts from the nassau train station

After talking with Jenna about the behind-the-scenes process of making Tottenville Sun, Tottenville Sky, I asked what it means to be in the enviable position of having art that’ll be on public display for decades, if not longer: “I love it. Because I want artwork, not just my artwork, but all artwork… it should be out in the public. It should be seen. It should be purposeful. So much artwork is like in these elite gallery spaces that people are literally afraid to go to. It's also only getting a certain demographic.” On New Years Eve Eve—just a few days before I interviewed Jenna—I was at the Philadelphia Art Museum, perfectly embodying this exact character of the fearful Philistine. It’s not that I don’t enjoy going to art museums, I just always end up feeling like I’m taking someone else’s space. Someone more worthy. There’s got to be more to appreciate than I can understand, more to know historically, technically, or even emotionally. And yet, there I was on vacation—my wallet $30 lighter—and so I decided that, instead of fighting my insecurity, I’d embrace it. I’d surrender. I’d let the art find me.

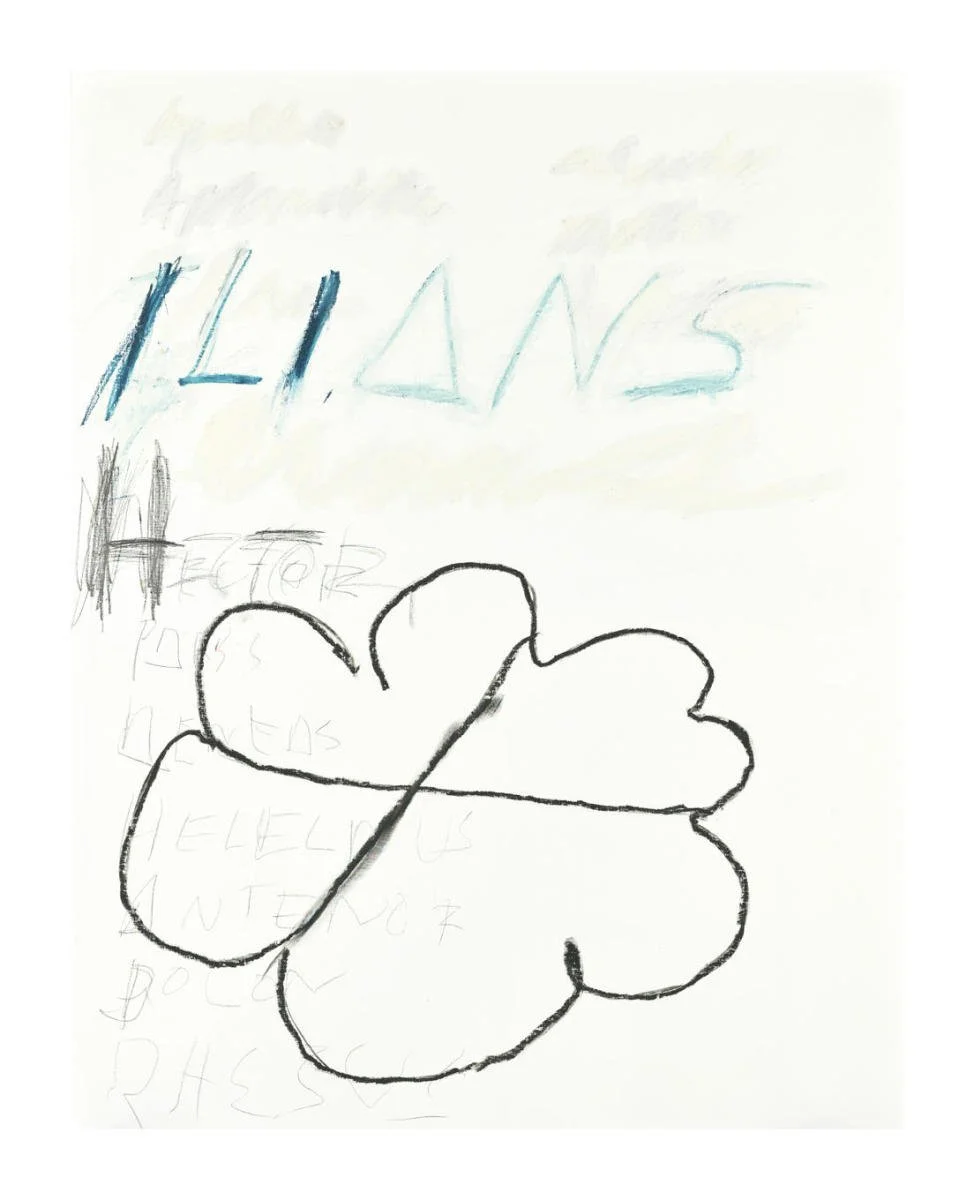

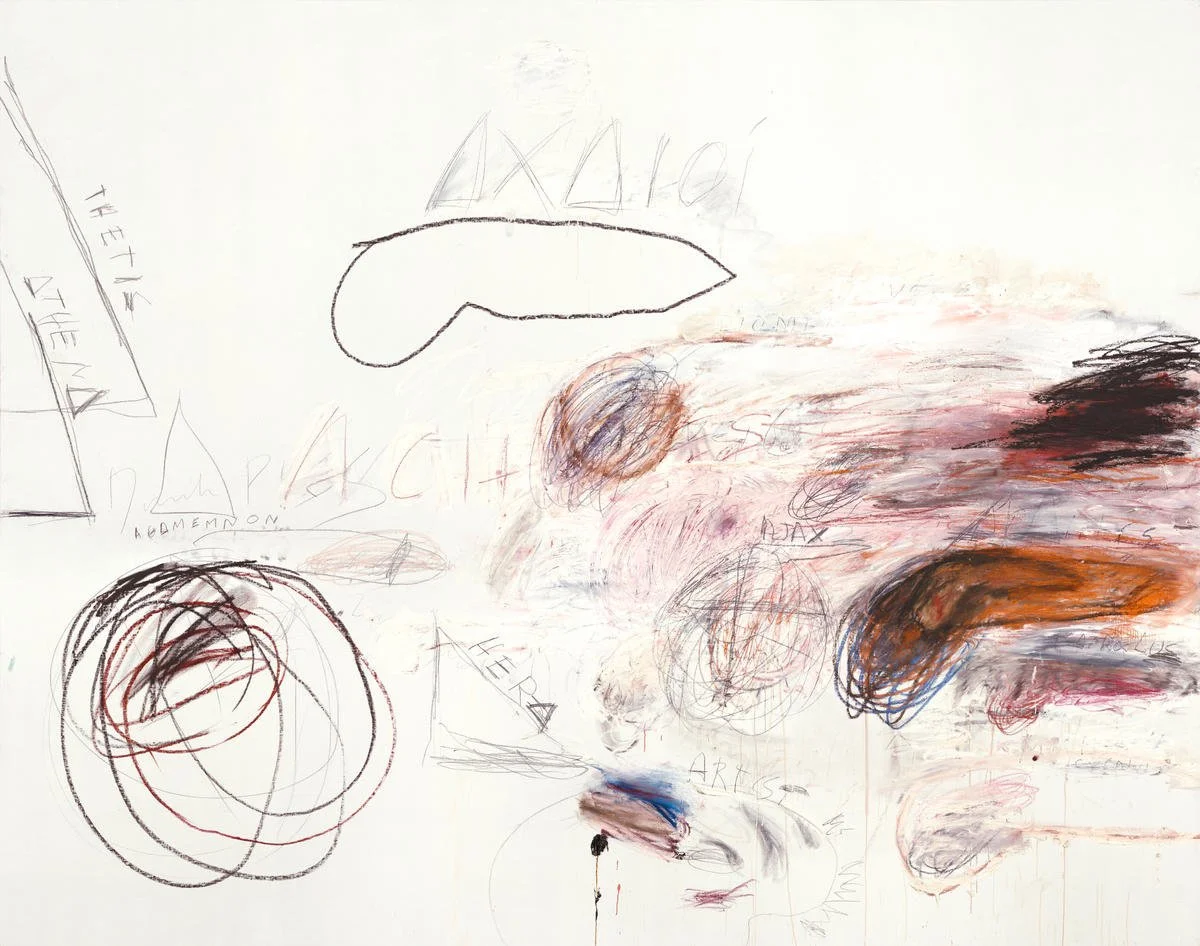

I saw: Prometheus Bound; Van Gogh’s Sunflowers; my first ever Kandinsky. What thoroughly baked my noodle for twenty minutes, however, was Cy Twombly’s Fifty Days at Iliam. I was drawn to these ten works instantly—I might have an uncultured peabrain, but even I can spot what is sure to be controversial art, the type of work that people label as “stuffy” because “my two year old can do that.” And I mean, c’mon, here’s the last piece, Heroes of the Ilians:

I entered the secluded room where these massive pieces were hung—purely for the lolz—and I was rewarded immediately: here’s Achaeans in Battle:

Seriously? Did I just spend $30 on some phallic graffiti??? How old was Cy Twombly when he made this, twelve????? Surely, I was being trolled by a juvenile. After recovering from my first impressions, I was slowly suckered into the work, much in the same way a good album can slip me into a new universe of its own construction. I lost all sense of time and self in front of this piece, The Fire that Consumes All Before It:

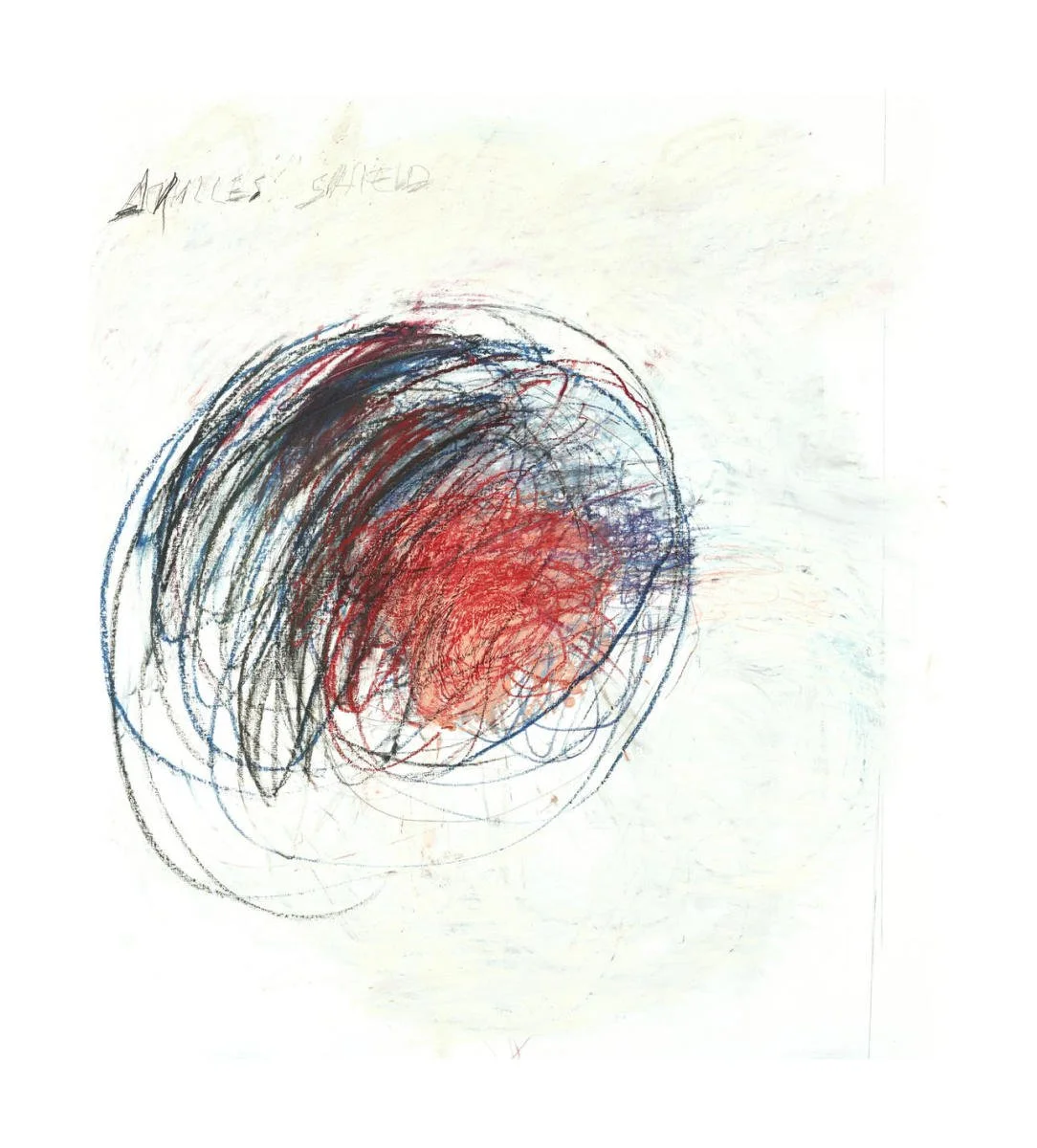

Cy Twombly was fifty—not twelve—when Fifty Days at Iliam debuted and, as the title suggests, the work is a reimagining of Homer’s Iliad. I found that out when I got back to my hotel and hopped straight onto the internet to do some research. This John Immerwahr video proved essential, helping me connect the dots ricocheting around my subconscious. Starting with: there was something more to the opening piece of scribbled circles, Shield of Achilles:

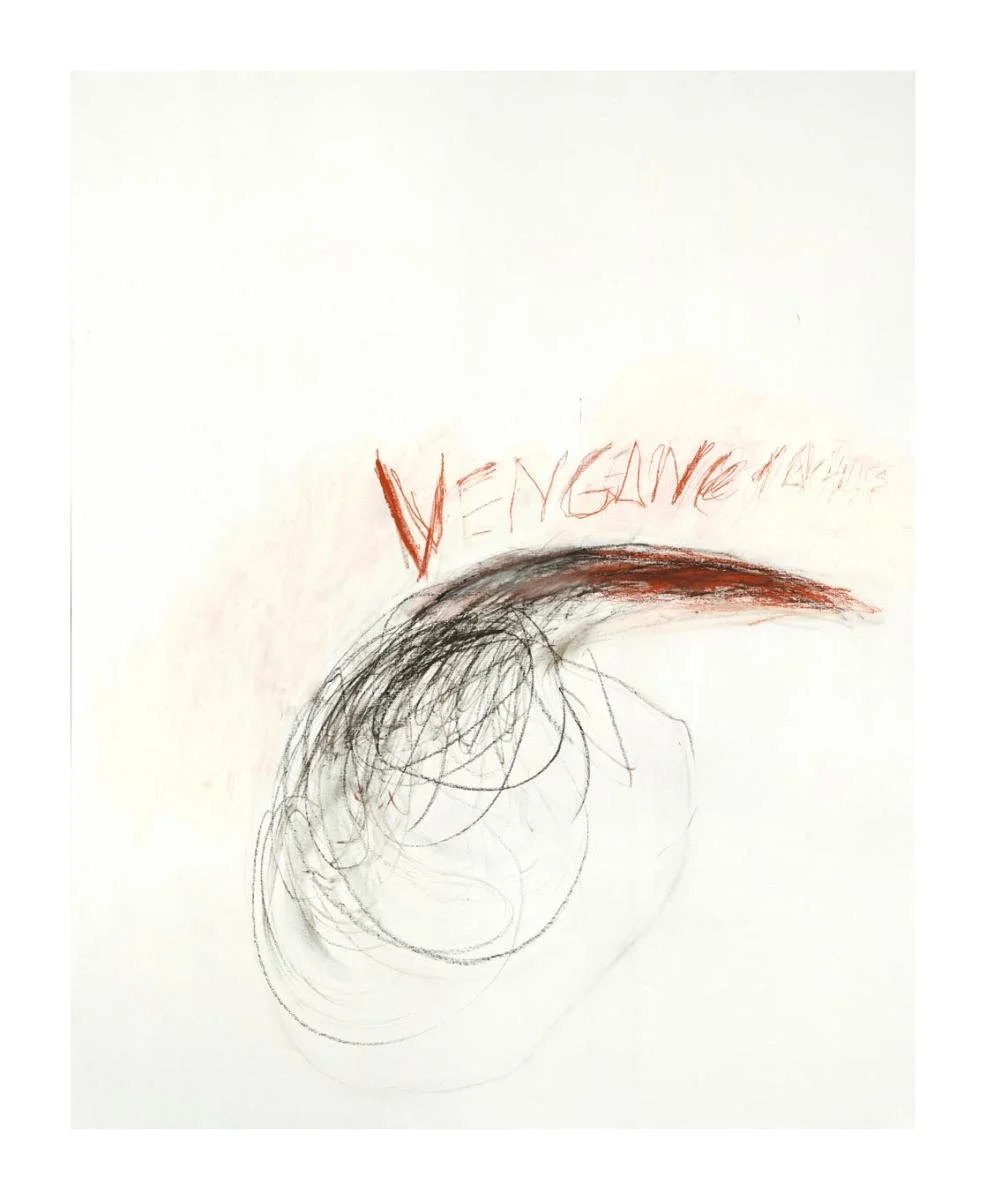

One the outside: the blue and black stone and metal of the shield, but inside—and barely contained—is Achille’s essence, the swirling, passionate rage. Bloodlust. Later on, Vengences of Achilles:

The shield cracks like an egg, and the rage pours out, taking, uh, shape. Achaeans in Battle follows right after. There are likely countless takeaways from Fifty Days at Iliam, as many as there are people that go to visit that cold room in the museum, I’m sure. My own, after sitting with my newly gained knowledge, is that the work is a profound statement on how—since the dawn of time—men have satiated their libidinousness with violence or vice versa (and often they are one in the same). I didn’t spell all this out to make that point, though, and my interpretation is just a detail. I mention all this because I don’t know if I ever would’ve gotten there on my own, and I hate that so often when I encounter art, I feel like I need to bust out the training wheels just to suss out what feels like my own truth coursing through me. My insecurity is legion, my doubt without limit.

“The art that's, for example, in all the subways—thanks to the MTA—it's for everybody. It is literally for everybody. It helps people feel connected to art. ‘Oh, I can understand this,’ right? ‘I get it. I saw art today.’” That was another reason why Jenna was proud of having public art—that anyone, including big, dumb idiot-heads like myself, can approach it without any trepidation. “Public art also needs to be accessible to people. It shouldn't be necessarily (in my opinion) some esoteric, high intellect, abstract concept piece, right? It needs to be relatable in some way. I hope that I have done that.”

Jenna has done that. I can vouch for it, and it’s why I appreciate it so much. There’s loads of MTA art that falls on the wrong side of that line for me personally, that I can’t engage with. But I can engage with the art at the Arthur Kill Station—my station.

Trains were an obsession of mine growing up. I had a trove of VHS tapes whose footage was little more than aerial shots of cargo trains going over bridges and traversing across bucolic, American landscapes. My father would make me custom wooden tracks for my junior playkit; I’d construct elaborate routes under tables and around couch corners. I stanned Thomas the Tank Engine and I still know every word to The Wee Sing Train soundtrack. In high school, I’d sometimes take a different bus home that’d swing by Prince’s Bay just to hop on the SIR there. This didn’t save me any time, I just liked riding the train. These days, I drool over fantasy SIR expansion diagrams posted on Reddit. You’d think, then, that when the news broke that Tottenville was getting a brand-spankin’-new train station in 2013, I’d have been ecstatic. The truth is that my reaction was complicated and mixed, a sentiment that hasn’t changed all that much in the near decade since the Arthur Kill Station’s grand opening.

I mentioned earlier that Tottenville used to have three stations. There was the eponymous Tottenville Station, but also the Atlantic and Nassau Stations. I never got on or off at the Atlantic Station. Once, early in middle school, I was walking along Ellis Street and mistook a snake for a wiggly twig near its entrance. Forever after, I deemed the whole place a snake pit, like something out of Raiders of the Lost Ark. Nassau Station, however… that was Shangri-La, the closest stop to my house. While I could get down there in under five minutes, it was the hours spent waiting, hanging out, and loitering that made it a part of me. That’s where I learned the virtue of boredom, the marvels it does for the mind, the heart, and the soul. And then one day it was gone, as the construction of the Arthur Kill Station gobbled up Nassau and Atlantic Stations.

Tottenville has many churches, but only one cathedral—that’s how I refer to the Arthur Kill Station. There’s so much glass! I mean, just look at Nassau Station when it closed and Arthur Kill Station after it opened.

It’s a celebrity glow-up after a rehab stint. The Arthur Kill Station is better in every way. Initially, I was going to say that it does have a downside—that it’s a little further from my house, and I have to cross a precarious section of Arthur Kill Road to get to it—but at my age, I can use the extra hustle, the extra exercise. So what’s my problem? Over the course of writing this piece, I’ve been trying to pin it down. The easy answer is I’m nostalgic for the “good old days,” but I know better. I know that people generally—and myself especially—remember the past better than it deserves. I’m not falling for that trap. I don’t want to “go back”—it's a different feeling than that.

I laid out the broad outline of this article to Jenna in the middle of our conversation, talking in depth about how crucial these spaces were for my peers and me. Jenna—who grew up on the North Shore—did not have access to the SIR, and only rode it later on in life to see what it was all about. A curiosity. Yet, she could still speak clearly to their enchanting, ritualistic power: “I think anytime you can provide something that gives people a shared experience, whether it's music, art, an event—anything—it helps people to bond and remember that we function as a society that works together, not apart. That's what I like to think about, and we need more of that. We're so isolated these days.” And what about the role of Tottenville Sun, Tottenville Sky is such a place? “[I hope] that it might slow people down, give them a quiet moment or two to just reflect. And also to be acknowledged that Staten Island was not forgotten by the MTA. That they were remembered and that, you know, care was put into that station just for them.”

The station cost tens of millions of dollars. It’s ADA compliant. Electronic screens deliver real-time scheduling updates. We were thought about. Considered. Some MTA board chose Jenna because she chose us when designing her work. Jenna spoke to this Herculean mission from the MTA, to, “[put] public art in places where there might not even be art, making the biggest museum that ever existed throughout all of these rail lines.” What I wouldn’t give to have had the Nassau Station be blinged out with all the trappings of the Arthur Kill Station, to have had it be the backdrop to my formative moments.

What’s always bothered me—I can identify now—is that I doubted the Arthur Kill Station as serving as the backdrop to anyone’s formative years. Jenna shared this anecdote: “One of my favorite stories of the MTA project was that when the project was getting unpacked, [when] the glass was getting unpacked, all the construction workers were totally into it. They were like, ‘Oh yeah, that's the this, that's the other thing, oh look, there's that.’ I was like, ‘I have done my job if they can recognize what they're seeing.’ … Every single thing that's in this design comes from the area.” I love this story, but at the same time it raises a heartbreaking question: do the kids in Tottenville have that same recognition? I don’t ride the train nearly as often as I used to, but when I do, I don’t see any young people hanging around. I see kids wandering around town—sometimes as menacing, wheelie popping biker gangs in the middle of Amboy Road—but mostly in wandering packs. And the difference between these packs and the lion prides of my youth is that most of them are buried in their phones.

If I come across as the old-man-yelling-at-the-clouds or a raving alarmist, so be it. But like, damn! Even I spent the whole first part of this article talking about video games and their expansive, fun worlds to explore from the tidy convenience of my couch. Math tells us that some infinities are bigger than other infinities; why would The Youth™ explore the world around them when the universe exists in their pocket? When I wrote earlier and advocated for/imagined a city with all free transportation, the idea gave me butterflies. I pictured myself with the near-frictionless exploration—prehaps as a high schooler, before I inherited my sister’s old, green Jeep, I might’ve taken a bus into the city to an art museum and developed enough experience that, later in life, I could be better at absorbing abstract art and forming my own concrete thoughts from it. But would the sons and daughters of Tottenville do something like that today? Have others ever made the trek down here and cross-pollinated in a little cultural exchange via what meager public art we do have? Even if we make these modes of transportation actually free, that doesn’t guarantee that it’ll make Staten Island’s cultural bridges toll free.

I wondered if there’s anyone out there today, some kid that can so easily anthropomorphize the Arthur Kill Station like I do with the Nassau Station. Today, I’ll name it my teacher. With nothing to do, I would go down to the station and learn. To be sure: sometimes riding the train was the plan, full stop. But more often than not, it was just something to do. Something kinetic. What I learned was that even with nowhere to go, you can’t ride a train without feeling you’re heading somewhere you’re supposed to be, even if that’s somewhere to get lost. In death, Nassau Station still lingers rent free in my mind, providing one more lesson: that things not only end, they disappear, and over time it’s like they never even existed. All that happened there? No they didn’t. For a time, after the train platforms were closed up, you could still use the overpass, but eventually that was taken away, too. Today, there’s a newer, incongruous fence—a section of it too clean and shiny, wedged between wire that has seen too much sun and wind and rain and dirt. At some point, it dawned on me that I see this sort of thing constantly: the difference in paved sections on a highway or the polished street signs with a new font, each of them a totem of something that’s been replaced. Context determines if this makes something better or worse, but regardless: I cannot interface with the world without this newfound lens. I don’t know if I ever would’ve gotten this perspective if I didn’t once have a cherished, deteriorating train station replaced with a shining castle.

This was the concession that I carried with me as I ventured across Tottenville doing my art survey, ending, naturally, at the Arthur Kill Station. Bummer! This marvel of engineering, this dedicated shrine to us, underutilized as far as I knew. What a shame, I thought, that this place could be a platform not only for entering a train, but to springboard character growth and seed wonder. I did not see any high schoolers there, just as I never do. I took my photos of Tottenville Sun, Tottenville Sky and, for the first time ever—on a pure whim!—walked back down the zig-zagging ramp instead of the stairs, the long way.

And that’s when it appeared to me, a Christmas gift. I saw—and nearly missed!—all the evidence for justified hope I needed: that juvenile delinquents did, in fact, loiter at the station, probably after hours, probably in a pack. At first I rolled my eyes, but then I laughed and snapped a photo, one I’m sure Cy Twombly could appreciate.

Yeah. The kids are all right:

Brian Buchanan is a physics teacher by day and, by night, a masked vigilante versatile artist. His passions span the realms of football, guitar pedals, & the law of large numbers. Brian finds beauty in the patterns of the universe, and his artistic soul is reflected in both his music and writing, where he weaves melodies and stories that touch the heart. At home, he finds inspiration and comfort in the company of two pups: Boo & Jem. Brian's gentle spirit and insights leave an enduring mark on everyone he meets (hopefully!!), making Shaolin a more beautiful place through his diverse talents.